It began with a call from a friend working at the downtown Sioux Falls public library. She had received an information request from someone on the east coast about a long-dead local attorney, my great grandfather, Joe Kirby. She wondered if I would be interested in talking to the person. As the unofficial family historian, I was certainly open to the request.

The researcher turned out to be Thomas Healy, a professor at Seton Hall Law School. He was working on a book about Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and the history of free speech in America. Holmes is recognized as one of the most influential judges in US history. Healy had uncovered a previously unknown and unpublished Supreme Court case in Holmes’s recently released private papers. Which led him to me.

My great grandfather was apparently involved in this case which I had never heard about in family lore. But I wasn’t surprised since Joe was perhaps the most active trial attorney of his era in our state. He handled hundreds of cases before our state supreme court and half a dozen at the US Supreme Court. Nevertheless, this case turned out to be quite an unusual story.

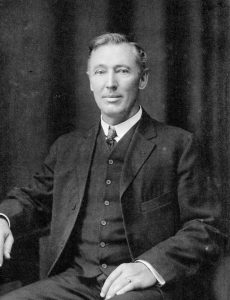

Sioux Falls attorney Joe Kirby in about 1917

The Espionage Act and World War 1

Our nation was at war in 1917. But support for the war effort was not universal and the government felt it was necessary to make certain types of speech illegal, such as advocating resistance to the draft or supporting America’s enemies. As a result, Congress adopted the Espionage Act of 1917 to suppress opposition and subversive activities.

The First Amendment to our constitution provides that Congress shall not make a law limiting the freedom of speech, the press, the right to assemble peacefully or the right to petition the government. The Espionage Act imposed significant restrictions on basic First Amendment rights, something that had never been done in our nation’s history. So everyone was curious to see what the courts might do with these new restrictions.

The Supreme Court interprets the constitution and laws passed by Congress. Once it has done so, a precedent is set for all lesser courts to follow as they handle similar cases. So, as the first Espionage Act cases approached, the government had a big stake in how the Court would interpret the new law.

The first Espionage Act case argued before the Supreme Court happened to be from South Dakota. In 1917, thirty German socialist farmers from Hutchinson County, South Dakota signed a poorly drafted and ill-advised petition to the state’s governor criticizing the military draft and requesting a change in the selective service laws. Understandably, they didn’t like the fact that their German blooded sons were being forced to fight their relatives back in Germany.

The federal government immediately charged the farmers with violating the Espionage Act. They were convicted in federal court and shipped off to Leavenworth prison. Their attorney, Joe Kirby, appealed the convictions to the US Supreme Court. What happened next was a big surprise.

Surprise at the Supreme Court

Over the period of two days, Joe Kirby argued for the defendants. One of the arguments he made was that no matter how poorly written or weak in thought the petition might be, if it was truly a petition by citizens to their government, it could not be prohibited by law. At the end of the day the nine justices met privately to discuss the cases argued that day, as was their normal practice. It was apparently clear the government would prevail in the case of the German farmers and one of the justices was assigned the task of writing the Court’s opinion.

When the draft opinion was circulated, Holmes didn’t like what he read so he drafted a short dissenting opinion and circulated it to the other justices. Two other justices, including the chief justice, joined Holmes in his dissent. Healy in his book on Holmes says, “What occurred next is one of the strangest episodes in Supreme Court history.”

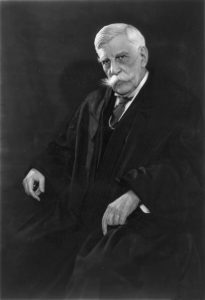

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Prosecutors somehow learned what was going on behind closed doors. That’s not supposed to happen. Supreme Court deliberations are confidential. They found out that while the Court was going to sustain the convictions, Holmes had written a persuasive dissent.

Prosecutors feared the Holmes’ dissent could be damaging to the prosecution of future Espionage Act cases. It was based on the argument Joe Kirby made, that citizens have a right to petition their government, even when the petition is poorly written. Other cases in the pipeline involved more obviously anti-American activities and speech. So, less than a week after Holmes sent his draft dissent to his fellow justices, the prosecution quietly confessed error. In other words, they dropped the case. This was an unprecedented situation.

The farmers returned to Hutchinson County and Joe Kirby to his law office. They apparently never knew why the charges were dropped, and perhaps they didn’t care all that much. Those cases were the only ones out of thousands prosecuted in which the federal government confessed error. The draft Court decision and Holmes’s dissent were never published and disappeared for decades until Holmes’s private papers were released in the 1990s.

Holmes’s opinions in the next three Espionage Act cases to reach the Supreme Court became landmarks in constitutional law. Over the next several months those three cases (Schenck, Debs and Abrams) with better fact situations for the government reached the Court. In each case, the convictions had been appealed based on the First Amendment and in each the conviction was upheld. The justices were reluctant to address the harm that the government’s handling of the war effort had done to the nation’s tradition of free speech. Nevertheless, in his series of opinions on these three cases Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. virtually invented First Amendment theory. And now there’s a fourth case which demonstrates his earlier thinking on the First Amendment.

Healy wrote his book on these cases, called “The Great Dissent”. It chronicles the evolution of Holmes’s thinking on the First Amendment and free speech, including the case of the German farmers from South Dakota. I also wrote a journal article about this case for the “South Dakota History” journal. I suspect great grandfather Joe would have been fascinated to hear how close his case came to being a landmark in American jurisprudence.

Healy’s book

Most interesting!

Is your dog named after Justice Holmes?

No, my mother’s maiden name was Holmes and she died shortly before we got the dog. Nice coincidence, though.

Fascinating piece, Joe–I thought when I was reading it that your great-grandfather had been the lawyer for Senator Pettigrew, who (as I recall) was also charged with violation of the Espionage Act, but obviously that wasn’t the case. But, regardless, he was on the side of the angels in standing up for free speech and the German socialist farmers from Hutchinson County, so good for him!

And, man, you’re close to the spitting image of your great-grandfather!

I think that this article should be shared in the SD Historical Society Journal or the SD Magazine.

Actually, I did write a journal article about this case for South Dakota History ten years ago. This is a shorter, more accessible version.

One has to wonder what your great grandfather would have to say about the more recent Patriot Act.

Thanks so much for this interesting piece of history. I suspect your grandfather might have not been very popular when he took this case.

Thanks for sharing this history, Joe! What a fascinating story!

Our state has a rich legal and political history, thanks for preserving it Joe.