State leaders propose cuts that starve local governments — the real reform lies in consolidation, technology, and accountability

South Dakota’s fiscal debates usually circle the same questions: whether to cut taxes, which ones, and who pays the price. Lately, rapid growth in residential property values has thrown the property tax formula out of balance. Instead of commissioning a serious study of how to fix it, some state leaders and candidates have floated proposals to cap or even eliminate property taxes. The idea sounds attractive on paper, but in practice it would destabilize the institutions most South Dakotans depend on, local schools, city services, and county governments.

Property Taxes Have Not Skyrocketed

At the heart of the matter is a misunderstanding of the causes of the pain some homeowners are experiencing. There is little indication total property taxes have taken an inordinate jump in recent years. Instead, an increase in home values has apparently distorted the formula for allocating property taxes between residential, ag and commercial property.

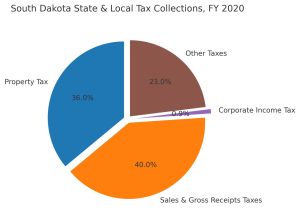

Meanwhile, state government lives mostly on sales taxes and federal transfers. Yet it is state officials and politicians, some with little to no experience in local governance, who are calling for property tax cuts while leaving their own revenue streams untouched.

A DOGE Effort in South Dakota Would be Misguided

This disconnect raises a larger question: What kind of reform does South Dakota really need? Businessman Toby Doeden, a political newcomer who wants to be governor, has suggested that he would “DOGE” state government, a catchphrase evoking the idea of slashing wasteful programs. But while such rhetoric resonates nationally, it misses the mark in South Dakota.

Unlike Washington, South Dakota’s state government isn’t awash in bloated agencies or ridiculous programs. Instead, it more closely resembles a struggling family-run shop: lean, underfunded, reliant on dated systems, and often vulnerable to inefficiencies or fraud. What the state lacks is not austerity but modernization. Outdated processes slow delivery of services. Fragmented structures increase costs. And the absence of coordinated, professional oversight leaves opportunities for improvement untapped.

Modernization and Consolidation Make Sense

A more constructive project would look less like “DOGE” and more like modernization and consolidation. Imagine a task force of seasoned executives from some of South Dakota’s best-run companies taking a hard look at state operations. With a mandate to find efficiencies, improve service delivery, and apply modern technology, such a group could identify changes that truly move the needle. The likely results: streamlined systems, smarter spending, and improved outcomes for citizens.

That is why proposals like Governor Larry Rhoden’s 2024 bill to cap property-tax growth, or Doeden’s talk of eliminating property taxes, feel misguided. These measures target the wrong level of government. Property taxes sustain local governments, which must balance budgets each year while maintaining schools, roads, and public safety.

When Pierre restricts their revenue without offering alternatives, the result is predictable: local officials are forced to cut programs or raise fees, shifting the burden in less transparent ways.

There is, of course, a more obvious option, one that almost no politician dares to talk about. South Dakota has too many governments. With 66 counties, hundreds of townships, and more than 150 school districts, the state maintains a costly system of governments with redundant and unnecessary facilities and employees. Consolidation of counties or school districts could lower administrative costs and deliver services more efficiently. Yet such structural reform demands courage, political will, and a willingness to confront entrenched local loyalties.

66 Counties in South Dakota

Creating Problems for Other Elected Officials

For now, state leaders and politicians prefer easier soundbites: cutting property taxes without tackling the underlying system. The contradiction is glaring. While protecting their own sales-tax revenue, state officials are restricting the lifeblood of local governments. The unanswered questions loom large: When revenues fall short, will the state step in with replacement funding? Or will school boards and city councils be left to close libraries, shorten school years, or defer infrastructure repairs?

Perhaps the better path for local government outsiders like Doeden and Rhoden would be to first gain hands-on experience in local government. Let them run a school district or a county commission, grapple with balancing budgets, and decide which programs to cut when dollars run thin. Only then will they appreciate the complexities behind the talking points.

Growing communities are hurt by Rhoden’s property tax limit

The real opportunity in South Dakota is not to starve local governments of revenue but to rethink how government at all levels operates. Modernization, efficiency, and consolidation, not blunt tax cuts, hold the key to a stronger, leaner state. What South Dakota needs is not a DOGE project, but a serious conversation about how to align its government structure with the realities of the 21st century.

Actually, property tax rates have been declining. But people complain because their property is more valuable.

Actually, Toby Doeden;s plan to get rid of the property tax completely, is great when you understand he wants to generate more tax revenue from out-of-state external moneys from, Banks and Trusts.

You are spot on regarding modernization. As a former member of Appropriations, I had a close up view of department budgets and processes. Our systems are ancient. Many are running on 80s technology. We have been updating but not in a methodical or systems project based way. I completely agree with your point regarding county and school districts. Most business can be conducted online. We don’t need 66 county seats. I remember your blog from a year ago where you described how we arrived at 66 counties.

When it comes to school districts it gets tricky. We don’t need 149 districts and towns won’t die if they lose their school. If they say that, the town is well on its way to death. I don’t relish the idea of students on a bus for two hours. However, we should look at leveraging our remote learning center at Northern U for those more advanced classes. We also need to leverage standard vendors for food, supplies, paper needs. Our BOR schools have done this successfully. We must need to ask ourselves: does each district in the Sioux Falls metro area need its own administration? Can we consolidate functions, maintain those after school activities, and save costs? Let’s get creative.

Finally, we need an ongoing tax/revenue oversight committee that is constantly reviewing our current revenue streams as well as expenses for the state, county, and city. This group should include some state legislators but more importantly we need tax experts, county, city, and school members. We also need business expertise.

This is just a start. The time is now. Do we have the political will to modernize?

Bill Janklow made a push to consolidate counties or school districts to deliver services more efficiently. I am waiting to elect a person with the courage, political will, and a willingness to confront entrenched local loyalties.

Actually, I was the one who raised the issue of consolidating counties when I was in the state legislature from 1997-2004. The opposition to the idea was overwhelming from the counties and other county officials. The main reasons I believe were both economic and cultural. The economic was one of simply job loss. The counties (I am generalizing) here and many cities depend on those county jobs for their economies. They felt that there would be a negative impact on their area. The cultural one was simply that people identified with the county they lived in and did not want to lose that identity nor lose their court houses. With all of the advancements in technology there may be some hope for the regionalization of government services but I hold out no hope for actual consolidation.

Bill Peterson

House Majority Leader 2001-2004 Member South Dakota House of Representatives 1997-2004

I think West Central, Brandon, Tea, Canton and Harrisburg should be all in the SF School District. Not only would we save millions, the students would get a better education with more options for classes.

As for property values, they are being artificially inflated which drives up our taxes. I have lived in my house for 23 years and my taxes have tripled and my home value has only doubled. They base my taxes on home sales on my block, which is silly since they have no idea what kind of value I have added to my home. The problem isn’t residential property taxes, the problem is Ag and Commercial are not being assessed at the same level as owner-occupied and if that gets fixed, we will have more property tax revenue then we know what to do with. You can’t bleed water out of a rock. Go where the money is; commercial property.

I also think business men should stay the HELL out of running governments. It is NOT the same as a for-profit business. If we want to make state government more efficient I would highly suggest we FIRE about half of the state employees in Pierre that don’t do much of anything. This is why our technologies have NOT been upgraded, that requires someone to do research and do actual WORK. There needs to be a full review of every single state employee, and I would recommend that review is handled by a private consultant.